Beyond the Billboards: Uncovering the Hidden Potentials of GLP-1 Medications

Jaqueline Rosenblum

Illustrations by Grace Buckles

Whether you’re watching the morning news on cable or streaming your favorite movie, odds are that you’ve seen advertisements for Ozempic, Trulicity, and Mounjaro — medications used to treat diabetes. Now, these pharmaceuticals have rapidly entered public awareness as weight-loss drugs, becoming major cultural talking points on social media, in celebrity interviews, and across medical headlines. Behind this growing buzz lies a complex biological story about how these medications actually work. Originally, GLP-1 medications were prescribed to people with type 2 diabetes, a disorder in which the body is unable to properly regulate energy use and storage, specifically involving how the body’s metabolic processes break down the simple carbohydrate, glucose [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. The key mechanism of these medications is glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), a hormone naturally produced in the intestines, pancreas, and certain brain regions [6]. GLP-1 plays a critical role in maintaining energy balance by stimulating metabolism, slowing digestion, and signalling fullness after eating [7, 8]. Today, GLP-1s have hit mainstream media following the discovery of their powerful weight-loss effects, but this is not the full story [8]. What’s left out of the advertisements you’ve seen is that GLP-1 also communicates with the brain by interacting with neurons — specialized cells that send and receive the electrical and chemical signals within the nervous system [9]. Though initially formulated and prescribed for the treatment of metabolic conditions like type 2 diabetes, evidence is growing regarding how GLP-1 agents may be repurposed for the treatment of brain conditions that threaten neuron survival [4].

Insulin and Glucagon: The Keys to Glucose Regulation

In the human body, an organ called the pancreas releases two important signaling molecules: insulin, which lowers blood sugar levels, and glucagon, which raises them [10, 11]. When you have not eaten for a while, such as while sleeping overnight, your blood sugar drops [11]. In response, the pancreas releases glucagon, which acts as a key to directly ‘unlock’ energy reserves in the liver, releasing glucose into the blood [11, 12]. Additionally, glucagon acts on fat cells to release fatty acids and on muscle cells to break down glycogen — the body’s stored form of glucose — thereby increasing the availability of glucose for energy conversion [11,12]. As you eat breakfast, your blood sugar rises, and the pancreas releases insulin, which becomes the new key that fits into a different set of ‘locks’ [11]. This set of locks opens specialized ‘doorways’ in the cell membrane through which glucose can be brought into the cell by transporters for use or storage [11]. If a person’s cells stop responding properly to insulin, they are said to have insulin resistance — a hallmark symptom of type 2 diabetes, where the ‘locks’ become jammed or the ‘keys’ are missing, leaving glucose stranded outside the ‘doors’ [3]. Before a patient with type 2 diabetes receives a management regimen to address chronic high blood sugar, they may notice symptoms such as increased urination, blurry vision, a drastic increase in thirst, and unexplained nausea [13]. Additionally, when left untreated or managed poorly, type 2 diabetes significantly increases one’s risk for other long-term health consequences [14]. Such complications include high blood pressure, heart disease, liver disease, stroke, loss of vision, kidney failure, painful nerve damage, and sores or ulcers [14]. Additionally, type 2 diabetes is associated with a greater vulnerability to infection, bone loss, joint issues, and muscle problems — all of which can become severe enough such that amputation is necessary to address the immediate issue [14]. Together, these complications can greatly reduce quality of life, making the management and reduction of insulin resistance crucial in treating type 2 diabetes [8].

Matchmaking: How GLP-1s Marry the Gut and Brain

GLP-1-based therapies act by binding to specific receptors, thereby enhancing insulin release and suppressing glucagon secretion in response to blood glucose levels [15]. While this mechanism regulates blood sugar and weight by slowing the passage of food from the stomach to the intestines, the impact of these drugs extends far beyond the digestive system [8]. GLP-1, in both natural and synthetic forms, plays a critical role in the gut-brain axis, a complex communication network linking metabolic function with the nervous system [16]. Because GLP-1 receptors are found in both the brain and throughout the rest of the body, GLP-1-based medications exert effects on various biological systems [16]. Interestingly, these drugs may offer neuroprotective effects by reducing neuroinflammation associated with both type 2 diabetes and neurodegenerative diseases [17]. Neuroinflammation is the brain’s response to injuries, toxins, and pathogens, which helps control damage, clear debris, and initiate healing [18, 19]. In neurodegenerative diseases, neuroinflammation becomes chronic as cells that regulate brain metabolism and immune response release inflammatory proteins, causing damage and leading to progressive neuronal degeneration [18]. The neuroprotective effects of GLP-1 medications are inspiring further research that could eventually position these drugs as promising agents for the treatment and prevention of neurodegenerative diseases [17].

Locking Away Memory: Understanding Alzheimer’s Disease

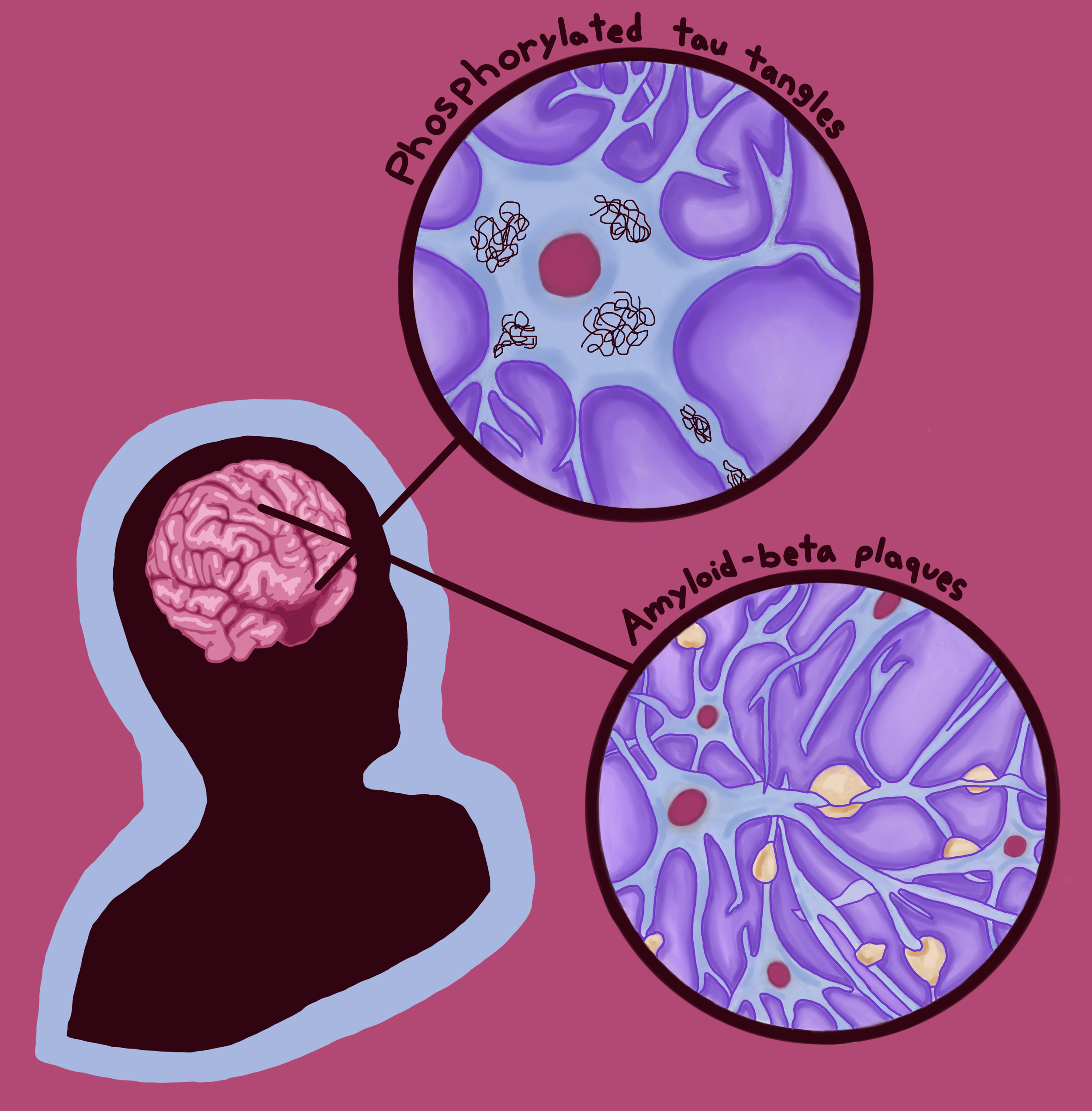

Dementia is a well-known umbrella term for several neurodegenerative conditions [20]. In fact, dementia is actually considered to be a pandemic condition among the aging population, with cases expected to double in the US and Europe over the next 25 years [21, 22, 23]. One disorder that falls under this umbrella is Alzheimer’s disease [20]. In its early stages, Alzheimer’s disease typically manifests as subtle changes in a person’s memory and thinking, such as forgetting recent conversations, struggling to make decisions, or becoming easily confused [24]. Over time, individuals may also experience shifts in mood or behavior, including increased irritability, episodes of verbal or physical aggression, and symptoms of depression [24]. Though there are no definitive conclusions regarding the causes of Alzheimer’s, there are two possible mechanisms that GLP-1s may manipulate to counteract this neurodegenerative condition [24]. The first mechanism is the buildup of two abnormal proteins: amyloid-beta proteins and phosphorylated tau proteins [24]. Amyloid-beta plaques are clumps of irregularly folded proteins that accumulate on the outer surfaces of neurons and disrupt cell-to-cell communication [24]. Additionally, the accumulation of abnormal tau proteins blocks the neuron’s internal transport system, impairing the movement of materials crucial for energy production and other cell functions [25]. The second mechanism contributing to Alzheimer’s development is impaired glucose metabolism, in which neurons cannot properly absorb and break down enough glucose to produce adequate energy [18]. The brain has two types of cells: neurons and glial cells [26]. Glial cells are neuron-supporting cells that regulate neural immune response and metabolism [26]. One key function of glial cells is their ability to turn glucose into fuel that neurons can use [26]. While the role of glucose metabolism in Alzheimer’s is debated, it is theorized that the amyloid plaques associated with the condition may prevent glial cells from converting enough glucose into sufficient fuel. This inconsistency reduces the energy available to neurons and may therefore reduce the production of chemical messenger molecules necessary for neuronal communication [18, 27, 28]. Conventional Alzheimer’s treatments aim to reduce the cognitive impairments that result from abnormal protein accumulation and deficiencies in glucose metabolism [18].

Uncovering the Connection: The Link Between Metabolism and Memory Loss

Synthetic GLP-1s are being considered as a new avenue for potential neurodegenerative disease treatments due to the growing evidence in clinical studies and animal models that type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s exacerbate one another [29]. People with type 2 diabetes are twice as likely to develop dementia, including Alzheimer’s [30]. In people with type 2 diabetes, neurons become less responsive to insulin due to a lack of insulin receptors and/or interrupted insulin signaling [31]. Because insufficient insulin response impairs glucose utilization, neural insulin resistance causes an energy deficit among brain cells [31]. The resulting metabolic irregularity could disrupt the processes that maintain a healthy balance of functional proteins within a neuron as well as its waste-clearing mechanisms, leading to the accumulation of amyloid-beta plaques and phosphorylated tau [29, 31]. These protein abnormalities may subsequently disrupt communication to insulin-producing cells in the pancreas, thus reducing insulin production and insulin sensitivity throughout the body, worsening neurodegeneration [29]. Because both Alzheimer’s and type 2 diabetes involve the buildup of misfolded proteins that interfere with cellular communication and metabolic stability, GLP-1-based therapies traditionally used to treat the latter may be a new way to slow — or possibly prevent — the progression of Alzheimer’s [17].

The synthetic GLP-1 drug, liraglutide, has been shown to demonstrate this benefit in animal models by preventing abnormal protein accumulation that would otherwise impair glucose metabolism in neurons, contributing to the presentation of Alzheimer’s [4]. As a result, classic Alzheimer’s symptoms seem to be reduced by mitigating learning problems, restoring brain signaling, and potentially even reversing memory loss [4]. One example of how these mechanisms counteract the symptoms of Alzheimer’s is evident in the way that connections between neurons in the hippocampus — a brain region important for memory formation — strengthen in response to GLP-1 treatment [6, 32]. As a result, the brain is better equipped to store new memories, retain information for longer periods, and organize information more effectively [32]. People with Alzheimer’s who take synthetic GLP-1s seem to maintain normal brain glucose metabolism and have more gradual cognitive decline, delaying the progression of Alzheimer’s symptoms [33]. By reducing inflammation and improving glucose metabolism in the brain, neurons can generate the energy needed to support the growth of stronger, more stable connections, thereby delaying the deterioration of cognitive function [6].

Fighting the Fire: Containing Parkinson’s Disease

Another potential application for synthetic GLP-1s is in the treatment of the neurodegenerative condition Parkinson’s disease [34]. Parkinson’s is characterized by motor and non-motor symptoms [34]. Motor symptoms can present as muscle rigidity, involuntary rhythmic shaking at rest, and difficulty maintaining balance [34]. On the other hand, non-motor symptoms may manifest as cognitive decline, sleep disturbances, and difficulty concentrating, along with dysfunctions that cause an abnormal heart rate and low blood pressure [34]. These symptoms are a direct byproduct of the degeneration of neurons within the substantia nigra, a brain region associated with motor control and coordination [35]. The substantia nigra contains cells that produce dopamine, a chemical signal that allows the brain to initiate and regulate smooth, intentional muscle movement [35, 36]. When dopamine levels drop, the brain’s communication with the body becomes impaired, leading to the motor symptoms that characterize Parkinson’s [35, 36]. Research into novel treatments for Parkinson’s disease is crucial, as it is the fastest-growing neurological disorder in the world [37]. Currently, Parkinson’s treatments are comparable to patches on a crack in the foundation of a house — current therapies manage symptoms and delay progression, but ultimately do not prevent the underlying disease [38]. As the number of people affected grows and neurodegeneration progresses, developing new approaches is essential to truly protect brain health [37, 38].

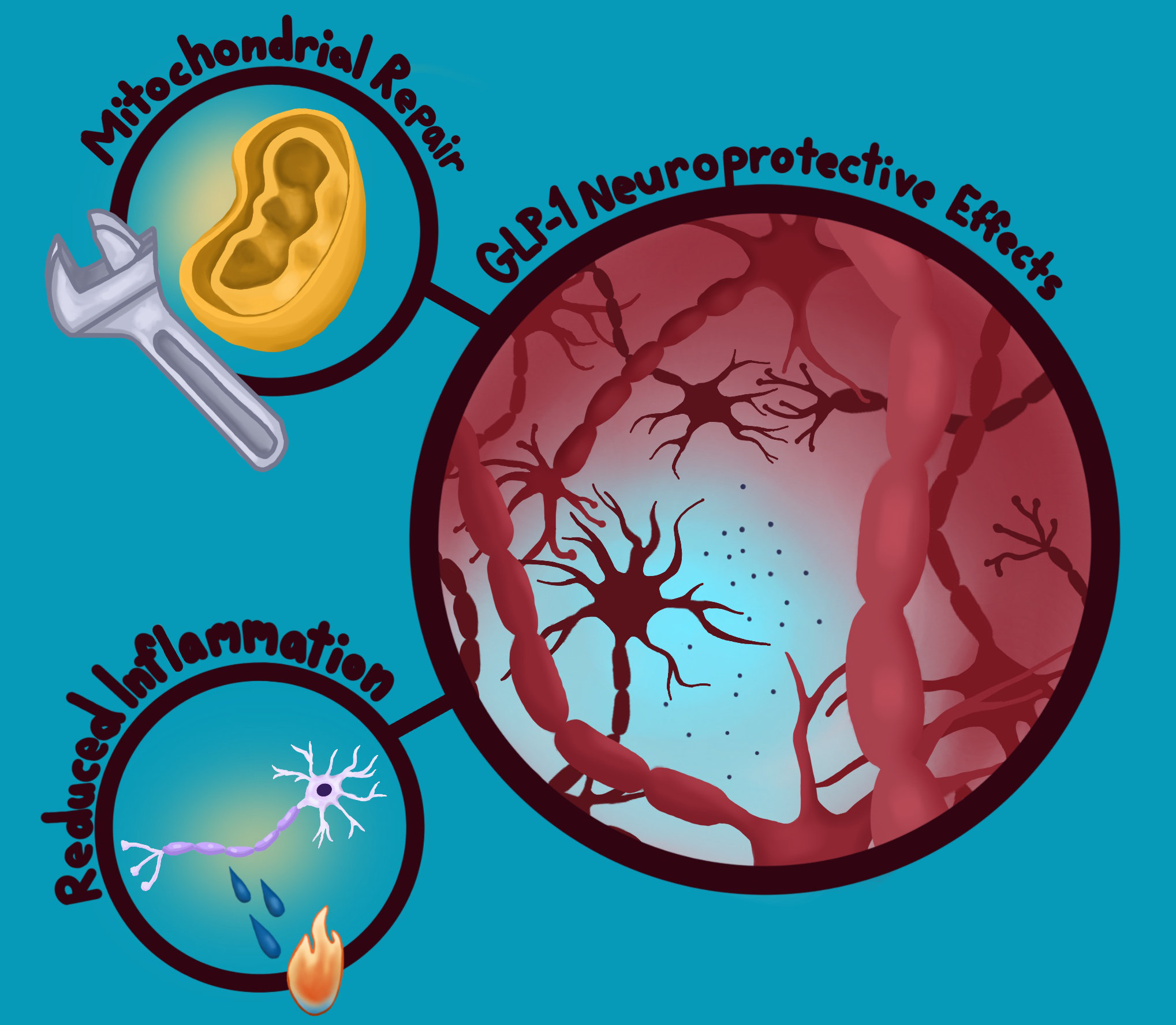

Fortunately, synthetic GLP-1s may offer new hope by protecting the brain in multiple ways [39]. One of their most promising effects is helping preserve the dopamine neurotransmitter system, as has been found in mouse models [39]. In Parkinson’s, the cells that produce dopamine slowly die off, leading to motor symptoms that impede daily functioning [39]. Because GLP-1s seem to shield dopamine-producing neurons to some degree, they can help those important neurons survive longer and function more effectively [39]. Beyond protecting the dopamine system, GLP-1s also appear to reduce harmful inflammation in the brain, as seen in Alzheimer’s mouse models [39]. Essentially, these drugs act as ‘firefighters’ containing a chronic ‘fire’ that gradually damages neurons [39]. GLP-1s support mitochondria, the cell’s energy factories, which become vulnerable in individuals with Parkinson’s disease [39]. In addition, GLP-1s may prevent misfolded proteins from building up and contributing to degeneration [39]. Because neuroinflammation, insulin resistance, and other biological mechanisms overlap across type 2 diabetes, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s, GLP-1s have the potential to offer meaningful effects beyond just symptom management for individuals with any of these conditions [17, 39].

Next Generation Neuroprotection: Dual Agonists Against Parkinson’s Disease

The use of synthetic GLP-1s as a treatment for Parkinson’s shows promise through the use of dual agonists — drugs that act upon two receptors rather than one [40]. Specifically, GLP-1s work closely with glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), a gut hormone that also stimulates insulin secretion and regulates appetite [41]. This dual-receptor activation mimics a more natural hormone response in the body, similar to how the gut normally uses GLP-1 and GIP signals together to regulate metabolism and cellular health [42]. In preliminary mouse model studies, DA-CH5 — a dual agonist drug designed to activate both GLP-1 and GIP receptors — stood out for its ability to provide therapeutic effects from the activation of both GLP-1- and GIP-related signaling pathways [43, 44, 45]. Once inside the brain, DA-CH5 appears to act like a ‘smart key’ by turning on only the GLP-1 and GIP switches without inadvertently activating any other systems, unlike insulin and glucagon, which act on systems throughout the whole body [45, 46]. DA-CH5 treatment may also help preserve neurons in the brain region most affected by Parkinson’s, delaying degeneration at least as effectively as existing treatments [45]. Beyond protecting neurons, DA-CH5 promotes processes that clear dysfunctional glial cells from the brain [45]. Typically, specific glial cells called microglia regulate neuroinflammation pathways by increasing inflammation in response to pathogens and by initiating cell death to clear abnormal or damaged cells from the brain [45]. In Parkinson’s, however, chronic hyperactivity of microglia induces long-term neuroinflammation and triggers a process in which the immune system mistakenly attacks the fatty membranes of neurons [45]. It is suggested that by activating both GLP-1 and GIP receptors, dual agonists initiate signaling processes that protect vulnerable neurons from immune attack, improve mitochondrial energy production, and normalize the breakdown of cellular material, ultimately providing broader neuroprotection than solely GLP-1-based drugs [45]. With their wide range of promising effects, dual agonists represent a powerful new direction for Parkinson’s treatment [43, 45].

GLP-1s: From Metabolism to the Mind

Although GLP-1 medications were originally developed to treat metabolic disorders like type 2 diabetes, emerging research suggests they may also play a valuable role in addressing neurodegenerative diseases [8]. Since they act on the gut-brain axis, reduce neuroinflammation, and protect vulnerable neurons, GLP-1s are being explored as potential disease-modifying therapies for various conditions, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, where current FDA-approved treatments remain largely limited to symptom management [4, 16, 17]. Despite this growing scientific interest, GLP-1 drugs remain widely known for their effects on blood sugar regulation and weight loss, yielding results that have fueled their rapid rise in popularity. Their presence in advertising, social media, and celebrity culture has transformed GLP-1s into a highly commercialized medical phenomenon — often overshadowing their broader, and still largely untapped, neuroprotective potential.

References

Lu, X., Xie, Q., Pan, X., Zhang, R., Zhang, X., Peng, G., Zhang, Y., Shen, S., & Tong, N. (2024). Type 2 diabetes mellitus in adults: Pathogenesis, prevention and therapy. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 9(1). doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01951-9.

Galicia-Garcia, U., Benito-Vicente, A., Jebari, S., Larrea-Sebal, A., Siddiqi, H., Uribe, K. B., Ostolaza, H., & Martín, C. (2020). Pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(17), 6275. doi:10.3390/ijms21176275.

Holst, J. J. (2019). The incretin system in healthy humans: The role of GIP and GLP-1. Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental, 96, 46–55. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2019.04.014.

Nowell, J., Blunt, E., & Edison, P. (2023). Incretin and insulin signaling as novel therapeutic targets for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Mol Psychiatry, 28, 217–229. doi:10.1038/s41380-022-01792-4.

Shendurse, A. M., & Khedkar, C. D. (2016). Glucose: Properties and analysis. Encyclopedia of Food and Health, 239–247. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-384947-2.00353-6.

Zheng, Z., Zong, Y., Ma, Y., Tian, Y., Pang, Y., Zhang, C., & Gao, J. (2024). Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor: mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 9, 234. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01931-z.

Salehi, M., & Purnell, J. Q. (2019). The role of glucagon-like peptide-1 in energy homeostasis. Metabolic Syndrome and Related Disorders, 17(4). doi:10.1089/met.2018.0088.

Drucker, D. J. (2018). Mechanisms of action and therapeutic application of glucagon-like peptide-1. Cell Metabolism, 27(4), 740-756. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2018.03.001.

Lovinger, D. M. (2008). Communication networks in the brain. Alcohol Research and Health, 31(3), 196-214. PMID: 23584863.

Karpińska, M., & Czauderna, M. (2022). Pancreas—its functions, disorders, and physiological impact on the mammals’ organism. Frontiers in Physiology, 13. doi:10.3389/fphys.2022.807632.

Röder, P. V., Wu, B., Liu, Y., & Han, W. (2016). Pancreatic regulation of glucose homeostasis. Experimental & Molecular Medicine, 48. doi:10.1038/emm.2016.6.

Rix, I., Nexøe-Larsen, C., Bergmann, N. C., Lund, A., & Knop, F. K. (2019, July 16). Glucagon Physiology. National Library of Medicine; MDText.com, Inc. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279127/

Brady, V., Whisenant, M., Wang, X., Ly, V. K., Zhu, G., Aguilar, D., & Wu, H. (2022). Characterization of symptoms and symptom clusters for type 2 diabetes using a large nationwide electronic health record database. Diabetes Spectrum, 35(2), 159–170. doi:10.2337/ds21-0064.

Farmaki, P., Damaskos, C., Garmpis, N., Garmpi, A., Savvanis, S., & Diamantis, E. (2020). Complications of the type 2 diabetes mellitus. Current Cardiology Reviews, 16(4), 249–251. doi:10.2174/1573403X1604201229115531.

Nauck, M. A., & Meier, J. J. (2016). The incretin effect in healthy individuals and those with type 2 diabetes: physiology, pathophysiology, and response to therapeutic interventions. The Lancet, Diabetes & Endocrinology, 4(6), 525–536. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00482-9.

Wachsmuth, H.R., Weninger, S.N. & Duca, F.A. (2022). Role of the gut–brain axis in energy and glucose metabolism. Experimental and Molecular Medicine, 54, 377–392. doi:10.1038/s12276-021-00677-w.

Green, C., Zaman, V., Blumenstock, K., Banik, N. L., & Haque, A. (2025). Dysregulation of metabolic peptides in the gut-brain axis promotes hyperinsulinemia, obesity, and neurodegeneration. Biomedicines, 13(1), 132. doi:10.3390/biomedicines13010132.

Adamu, A., Li, S., Gao, F., & Xue, G. (2024). The role of neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases: current understanding and future therapeutic targets. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 16. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2024.1347987.

Cheataini, F., Ballout, N., & Al Sagheer, T. (2023). The effect of neuroinflammation on the cerebral metabolism at baseline and after neural stimulation in neurodegenerative diseases. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 101, 1360–1379. doi:10.1002/jnr.25198.

DeLozier, S. J., & Davalos, D. (2015). A systematic review of metacognitive differences between Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias, 31(5), 381-388. doi:10.1177/1533317515618899.

Sadigh-Eteghad, S., Sahebari, S. S., & Naseri, A. (2020). Dementia and COVID-19: complications of managing a pandemic during another pandemic. Dementia & Neuropsychologia, 14(4), 438–439. doi:10.1590/1980-57642020dn14-040017.

Scheltens, P., De Strooper, B., Kivipelto, M., Holstege, H., Chételat, G., Teunissen, C. E., Cummings, J., & van der Flier, W. Alzheimer's disease. (2021). The Lancet, 397(10284), 1577-1590. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32205-4.

Singer, M. E., Dorrance, K. A., Oxenreiter, M. M., Yan, K. R., & Close, K. L. (2022). The type 2 diabetes 'modern preventable pandemic' and replicable lessons from the COVID-19 crisis. Preventive Medicine Reports, 25. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101636.

McGirr, S., Venegas, C., & Swaminathan, A. (2020). Alzheimer's disease: a brief review. Journal of Experimental Neurology, 1(3), 89-98. doi:10.33696/Neurol.1.015.

Zhang, X., Wang, J., Zhang, Z., & Ye, K. (2024). Tau in neurodegenerative diseases: molecular mechanisms, biomarkers, and therapeutic strategies. Translational Neurodegeneration, 13. doi:10.1186/s40035-024-00429-6.

Jha, M. K., & Morrison, B. M. (2020). Lactate transporters mediate glia-neuron metabolic crosstalk in homeostasis and disease. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 14. doi:10.3389/fncel.2020.589582.

Liu, L., MacKenzie, K. R., Putluri, N., Maletić-Savatić, M., & Bellen, H. J. (2017). The glia-neuron lactate shuttle and elevated ROS promote lipid synthesis in neurons and lipid droplet accumulation in glia via APOE/D. Cell Metabolism, 26(5), 719-737. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2017.08.024.

Yu, L., Jin, J., Xu, Y., & Zhu, X. (2022). Aberrant energy metabolism in Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Translational Internal Medicine, 10(3), 197–206. doi:10.2478/jtim-2022-0024.

Bharadwaj, P., Wijesekara, N., Liyanapathirana, M., Newsholme, P., Ittner, L., Fraser, P., & Verdile, G. (2017). The link between type 2 diabetes and neurodegeneration: roles for amyloid-β, amylin, and tau proteins. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 59(2), 421–432. doi:10.3233/JAD-161192.

Pruzin, J. J., Nelson, P. T., Abner, E. L., & Arvanitakis, Z. (2018). Review: relationship of type 2 diabetes to human brain pathology. Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology, 44(4), 347–362. doi:10.1111/nan.12476.

Arnold, S. E., Arvanitakis, Z., Macauley-Rambach, S. L., Koenig, A. M., Wang, H. Y., Ahima, R. S., Craft, S., Gandy, S., Buettner, C., Stoeckel, L. E., Holtzman, D. M., & Nathan, D. M. (2018). Brain insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer disease: concepts and conundrums. Nature Reviews Neurology, 14(3), 168–181. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2017.185.

Li, T., Jiao, J. J., Hölscher, C., Wu, M. N., Zhang, J., Tong, J. Q., Dong, X. F., Qu, X. S., Cao, Y., Cai, H. Y., Su, Q., & Qi, J. S. (2018). A novel GLP-1/GIP/Gcg triagonist reduces cognitive deficits and pathology in the 3xTg mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Hippocampus, 28(5), 358–372. doi:10.1002/hipo.22837.

Gejl, M., Gjedde, A., Egefjord, L., Møller, A., Hansen, S. B., Vang, K., Rodell, A., Brændgaard, H., Gottrup, H., Schacht, A., Møller, N., Brock, B., & Rungby, J. (2016). In Alzheimer's disease, 6-month treatment with GLP-1 analog prevents decline of brain glucose metabolism: Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 8, 108. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2016.00108.

Kalinderi, K., Papaliagkas, V., & Fidani, L. (2024). GLP-1 receptor agonists: A new treatment in Parkinson's disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(7), 3812. doi:10.3390/ijms25073812.

Costa, K. M., & Schoenbaum, G. (2022). Dopamine. Current Biology, 32(15). doi:10.1016/j.cub.2022.06.060.

Zhou, Z.D., Yi, L.X., Wang, D.Q., Lim, T. M., & Tan, E. K. (2023). Role of dopamine in the pathophysiology of Parkinson’s disease. Translational Neurodegeneration, 12. doi:10.1186/s40035-023-00378-6.

Dorsey, E. R., Sherer, T., Okun, M. S., & Bloem, B. R. (2018). The emerging evidence of the Parkinson pandemic. Journal of Parkinson's Disease, 8. doi:10.3233/JPD-181474.

Mahlknecht, P., & Poewe, W. (2024). Pharmacotherapy for disease modification in early Parkinson's disease: How early should we be?. Journal of Parkinson's Disease, 14. doi:10.3233/JPD-230354.

Lv, D., Feng, P., Guan, X., Liu, Z., Li, D., Xue, C., Bai, B., & Hölscher, C. (2024). Neuroprotective effects of GLP-1 class drugs in Parkinson's disease. Frontiers in Neurology, 15. doi:10.3389/fneur.2024.1462240.

Spezani, R., & Mandarim-de-Lacerda, C. A. (2022). The current significance and prospects for the use of dual receptor agonism GLP-1/glucagon. Life Sciences, 288. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2021.120188.

Fukuda, M. (2021). The role of GIP receptor in the CNS for the pathogenesis of obesity. Diabetes, 70(9), 1929–1937. doi:10.2337/dbi21-0001.

Liu, Q. K. (2024). Mechanisms of action and therapeutic applications of GLP-1 and dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 15. doi:10.3389/fendo.2024.1431292.

Feng, P., Zhang, X., Li, D., Ji, C., Yuan, Z., Wang, R., Xue, G., Li, G., & Hölscher, C. (2018). Two novel dual GLP-1/GIP receptor agonists are neuroprotective in the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Neuropharmacology, 133, 385–394. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.02.012.

Rizvi, A. A., & Rizzo, M. (2022). The emerging role of dual GLP-1 and GIP receptor agonists in glycemic management and cardiovascular risk reduction. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity, 15, 1023–1030. doi:10.2147/DMSO.S351982.

Zhang, L., Zhang, L., Li, Y., Li, L., Melchiorsen, J. U., Rosenkilde, M., & Hölscher, C. (2020). The novel dual GLP-1/GIP receptor agonist DA-CH5 is superior to single GLP-1 receptor agonists in the MPTP model of Parkinson's disease. Journal of Parkinson's Disease, 10(2), 523–542. doi:10.3233/JPD-191768.

Petersen, M. C., & Shulman, G. I. (2018). Mechanisms of insulin action and insulin resistance. Physiological Reviews, 98(4), 2133–2223. doi:10.1152/physrev.00063.2017.